The New York City Parks Department would probably want me to start this way: North Brother Island is a ruin. It hasn’t been occupied, nor used for anything by anyone except nesting herons, since the early 70’s. Thus, it’s dangerous.

At best, you’ll probably walk away with a case of poison ivy. (We were spared somehow.) At worst, you could fall down an open utility shaft. The disused hospital where the city used to isolate tuberculosis patients is crumbling and may be rife with asbestos. Same with the other former medical buildings on the north end of the island. Even walking around is a chore. The whole place is choked with kudzu and porcelain berry. North Brother Island is what will happen to the whole of our civilization when humanity is dead.

![]()

Sean on North Brother Island

But I’m actually going to start this way: North Brother Island is more fascinating by accident than most intentionally fascinating places are. It feels as though one day, everyone living and working there just dropped everything and left. It feels as much like that day was yesterday as it feels like it was 100 years ago. The hospital smells medicinal, maybe from all of the x-ray film piled up on the floor of the x-ray room. Random fire hydrants and lamp posts stick up through the thickets and weeds – but soon you realize there’s nothing random about it. There are roads under all that thick overgrowth. And curbs. A curb is so urban a thing this place can’t have ever claimed one, but it did. Roofs and basements should never meet each other, but they do here.

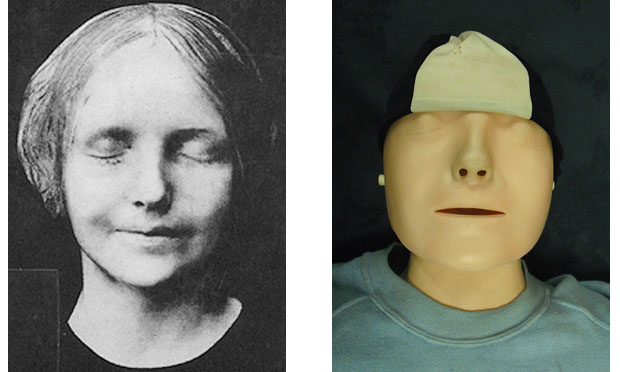

![]()

A collapsed building on North Brother Island. Mary lived in a cottage near this spot while under quarantine.

We visited this island for our story on Typhoid Mary. She was quarantined here and we wanted to find her cottage. (It doesn’t exist anymore.) North Brother Island is so close to the city I figured you could just canoe to it. And you can. If you want to be arrested. To visit the island you must:

1) Contact the parks department. They don’t even let themselves visit the island most of the time. March to October is off limits. That’s when the herons nest.

2) If the parks department gives you permission, you have to charter a boat, which can be really expensive. To make it more affordable, find other folks who need to visit and split the cost with them.

3) Thing is, a big group requires a big boat and a big boat can’t dock on the island. There’s no dock. We had to tie off on a rotting piling, motor over in a smaller boat, three by three, and beach ourselves onto the sand. In short, to get to North Brother Island, you have to mildly shipwreck yourself.

![]()

We think these quarters were used by nurses on the island.

What to do first:

If you’re pressed for time, explore the buildings first. From the spot where you beach, the hospital is straight ahead and to the left. (Ignore the broken, tilted awning above the entrance that says “Christian Center Sanctuary of Hope.” It’s a practical joke/art project.) But the hospital isn’t even the creepiest place. The creepiest place is (what we think was) the “Nurse’s Home.” Bullet holes perforate an outer door – all exit wounds. All the theater seats in the entertainment hall have collapsed. The curtain runner above the stage would still work were there a curtain. The wall switches still move up and down, with that loud, mid-20th century “tock.”

![]()

The abandoned theater.

![]()

A porch in disrepair.

Still, the hospital is pretty incredible. We walked through the wards where TB patients were quarantined. Private rooms were available too, including one with bars on the windows and a door slot through which maybe food was delivered. Whoever was treated in there can’t have been very stable. In one of the offices, there are mimeographed handouts strewn across the floor as though a receptionist had an apoplectic fit and quit on the spot. “STUDIES ON ADDICTION FROM RIVERSIDE HOSPITAL,” they say. After this was (in essence) a leper island, it was a drug rehab facility.

![]()

Sean inspects a hospital room.

![]()

The view from the hospital room.

What to do next:

Walk south toward the lighthouse, past the smooshed chapel that looks like the house that landed on the witch in the Wizard of Oz. Keep an eye on the water until a sparkling view of Manhattan emerges. Seeing the city from this remove is a little like seeing Earth from the moon – especially if you imagine you’re Mary Mallon and aren’t allowed to go home, no matter how much you plead or cajole the doctors who are constantly testing your stool. It doesn’t feel like any place in the East River should ever have been so built up and inhabited, let alone so abandoned and allowed to melt down like this.

![]()

View of Manhattan through a broken fence.

Whatever you do, remember you’re one of a rare breed of people who have seen North Brother Island. So count yourself lucky. Oh, and take lots of pictures. Like our producer Lynn Levy did. This is Lynn:

![]()

Lynn Levy braving the ruins.

Thanks Lynn.

It's a particular kind of tree sap, from the border area between Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand. It takes years to collect a big enough blob to sell to paint suppliers. And in the course of those years, the sap collects a souvenirs of the things happening around it. Robert and producer Sean Cole headed to

It's a particular kind of tree sap, from the border area between Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand. It takes years to collect a big enough blob to sell to paint suppliers. And in the course of those years, the sap collects a souvenirs of the things happening around it. Robert and producer Sean Cole headed to

Perched in a duck blind in a wildlife research center outside of Washington, D.C.,

Perched in a duck blind in a wildlife research center outside of Washington, D.C.,